Nothing is more frustrating than hitting the trigger on an air tool and a stream of water comes out the exhaust port. But, where did it come from? What can be done to prevent it from getting to your tools?

Nothing is more frustrating than hitting the trigger on an air tool and a stream of water comes out the exhaust port. But, where did it come from? What can be done to prevent it from getting to your tools?

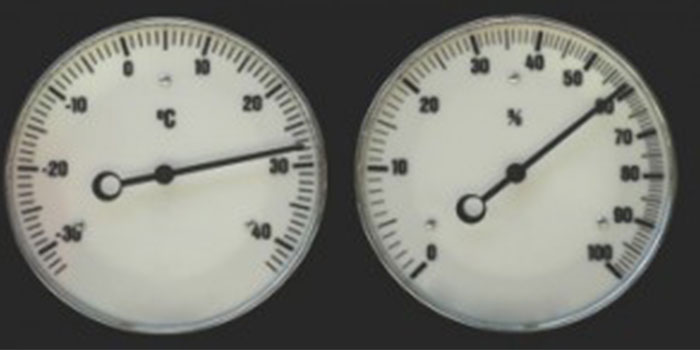

Water is all around us. It is in the form of vapor mixed with collection of gases we breathe. How much water is in the air is dependent on temperature and how much is present in the environment.

And while you can’t control the weather at your shop, you can control the quality of the air coming out of the compressed air lines with a couple of compressor strategies.

Temperature

The amount of water held in air is dictated by temperature. It is simple physics that hot air can hold more water (as vapor) than cold air. At higher temperatures, water molecules are more likely to go into the vapor phase, so there will be more water vapor in the air.

When the air cools down, the water has to go somewhere. If you were to graph temperature against humidity, where the two lines cross would be called the dew point. At this point the air becomes saturated and the water condenses into droplets. Dew points can occur at 200° or 32°, depending on relative humidity and temperature.

In the case of a shop’s air compressor, the air in the compressor room maybe as high as 130° and the air coming out of the lines in the shop maybe 80°. During this drop in temperature, chances are a dew point will be crossed. When this happens, water droplets form in the compressor or the lines.

Solutions

You can’t shut down your shop on a humid day, nor can you afford down time due to malfunctioning air tools. You can help to eliminate problems by controlling the temperature of the air going into and out of the compressor.

Look at where your compressor breathes. If your compressor can’t pull in cool and dry air, it is already handicapped. If your compressor is in a small room that receives inadequate ventilation, it can increase intake temperatures and the amount of water in the intake air. A little ventilation from an exhaust fan can go a long way to lower temperatures and water.

Most professional-level compressors use the strategy on lowering air temperatures on the output side of the compressor. This has been traditionally done with finned lines from the compressor to the tank. The goal is to cool the air enough so water condenses in the tank.

In theory, no water droplets would make it to the tools. It works if the temperature drop from the tank to the tool is not great enough to cause the dew point to be reached. But, with longer airlines, it is possible to get enough of a temperature drop to get condensation.

Some new compressors have refrigeration units that cool the compressed air and draw out the moisture so the dew point is the same from the compressor to tool. These coolers or dryers can chill the air to an adequate dew point so the water stays in the compressor room and out of the lines. While refrigerated compressors can be more expensive, they can eliminate down time and water in the lines.

What About Water Separators?

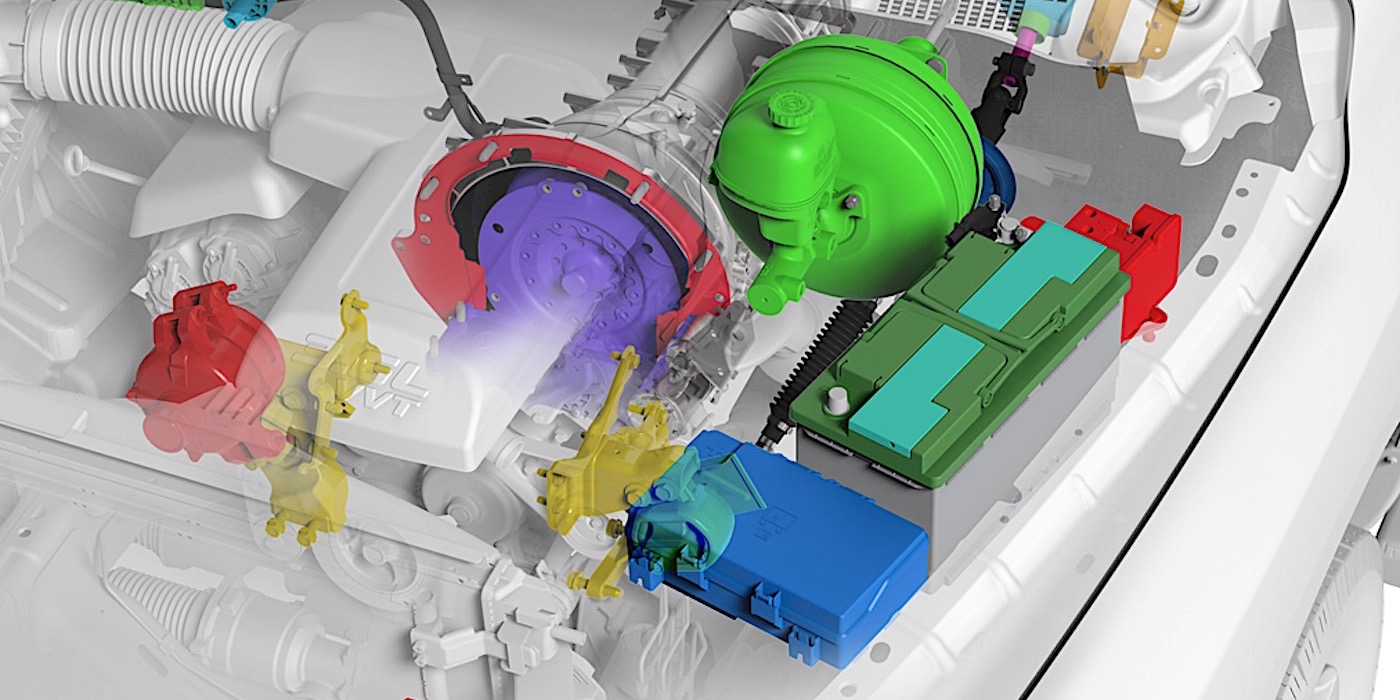

Water separators should be located as close to the air tool as possible and before any pressure regulator. A separator uses centrifugal force to remove water droplets from the air. Air is spun around the chamber and the rotational forces propel condensate droplets toward the separator wall from where they flow into the collection chamber. Units should be drained at the end of the day to prevent water from making its way to your tools.

Courtesy Underhood Service.