Bleeding the brakes is a procedure that’s performed to remove air from the system when a component is replaced, and one that’s performed strictly from a maintenance standpoint of flushing or changing the brake fluid. The telltale symptom of air in a brake system is a soft or “spongy” pedal, along with poor brake performance.

The idea and basic process is generally understood: You must get all the air out for the brakes to work properly. Air compresses and fluid does not, so even the tiniest amount will affect brake operation. Bleeder screws at each wheel allow the air to be forced through and out. If the idea sounds simple, it is, but it’s not without the occasional headache.

The key is that not every system responds the same, and you may need to bleed one differently than another. There are a few different methods you can use, and while it often comes down to preference, it pays to be familiar with them all.

The most important thing, however, is your mindset. Don’t think about brake work and bleeding as two different things. Instead, when performing any brake work, think ahead about bleeding and prepare for it. It always should be a part of brake work, as opposed to leaving it as an afterthought.

At minimum, brake fluid should be replaced/flushed every two years. The older it gets, the more moisture it absorbs, the worse it performs and the more corrosive it gets – slowly eating away at the expensive internal components of a brake system. When replacing brake pads, the caliper pistons must be pushed back into

the caliper.

The most common practice is simply to push them back with whatever tool you have at your disposal and remove any excess fluid from the master-cylinder reservoir, but this isn’t the best way to do it. The proper way is to open the bleeder screw prior to pushing the piston back in and let the old fluid be pushed out.

When you force it back into the master cylinder, you’re forcing contaminants and particles back past the master-cylinder seals, which can potentially damage the seals and lead to premature failure. In short, if you’re working on the brakes, get that old fluid out of there!

Bleeder Screws First

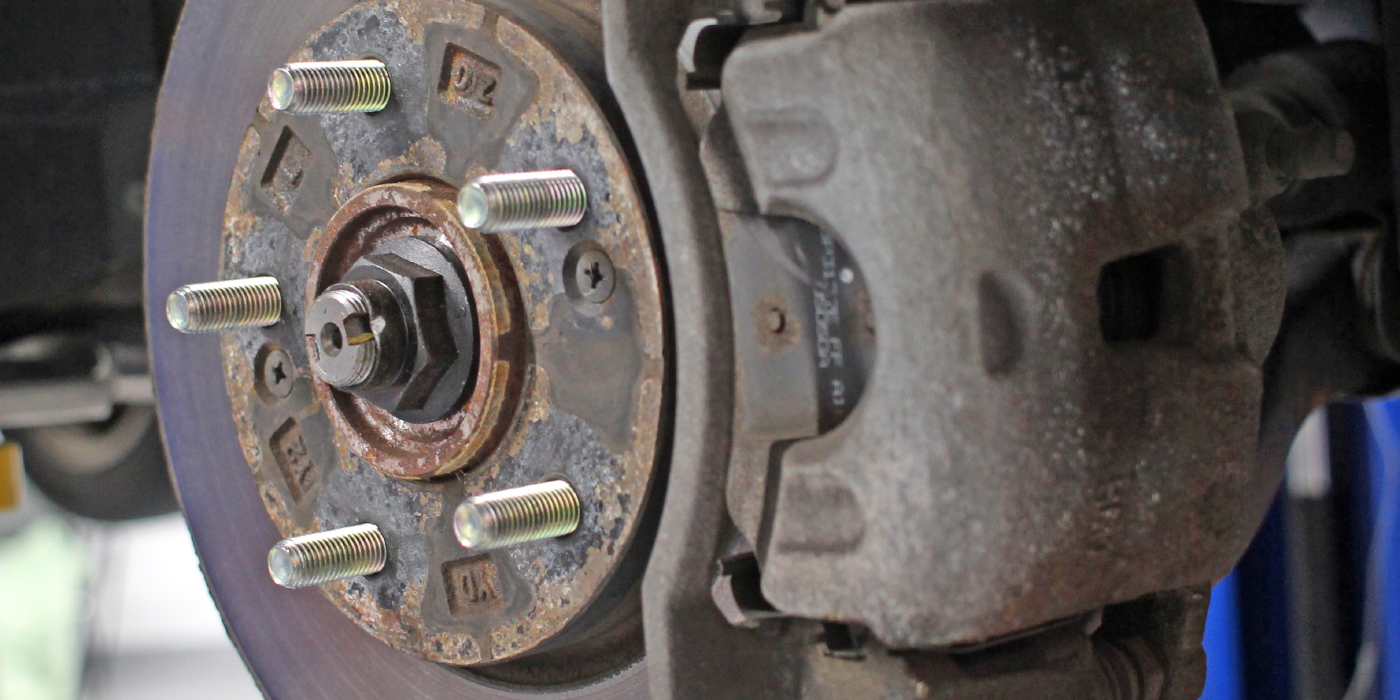

The first thing I always do with any type of brake work is check all the bleeder screws and make sure they open. If they’re stuck, regardless of what needs to be done to loosen them – be it heat, penetrating oil or another form of persuasion – now is the time to do it. If you ultimately have one that breaks, you can plan to replace that component as part of the job, instead of waiting until the end only to have one break when you’re

almost done.

Once you’ve opened the bleeder screws, take the additional step of removing and cleaning them. Spray brake cleaner into one end to make sure they aren’t plugged up with dirt or rust. Be sure to wear safety glasses – it often sprays back in your face if they are. Brake fluid should also drip out of the caliper or wheel cylinder, so be prepared with a drain pan underneath. It may not be a lot, but you should see at least a little fluid.

It’s not so important at this step that a lot of fluid comes out, but make a mental note of it. If no fluid comes out, there may be blockage in the caliper or wheel cylinder. It’s not uncommon for rust to form in the bleeder port and keep anything from coming out, even with a clean bleeder screw. If you run across this, it’s a problem that’s easily remedied using a small pick to poke through the rust.

Once you’ve confirmed that all bleeders open and fluid can flow, you’ve set the stage for a successful bleed of the system – but make sure you haven’t overlooked any bleeder screws. Most vehicles have four (one at each wheel). Some four-piston calipers have two bleeder screws each – one on the inboard side and one on the outboard. They both need to open.

Occasionally you may run across a vehicle with a load-sensing proportioning valve in the rear (usually on trucks) that has an additional bleeder screw on top. This can really throw you for a loop because they’re often out of sight. If you don’t bleed the air at this location, you’ll never get a good pedal. The bottom line is to locate all bleeder screws, and make sure they all open and flow freely.

Bleeder screws are located at the high point of a brake caliper, but it’s possible to install some calipers on the wrong side. This is a very common mistake and when it happens, the bleeder screws will be on the bottom. It’s impossible to bleed the system like this, so if you run across it, you’ll have to remedy the situation beforehand.

The ‘Standard’

“Pump it up and hold it!” For most of us, our experience bleeding brakes began as a helper. You pump the brake pedal a few times and hold it. Then the person doing the work opens a bleeder screw. When the pedal reaches the floor, you report “on the floor.” The bleeder screw is then closed, and the process repeated until all air is forced from the system, and you report a good solid pedal.

To properly perform the procedure, you start at the bleeder located furthest from the master cylinder, then finish with the bleeder closest – in other words RR, LR, RF then LF. This method, often referred to as “manual” bleeding, has been the standard procedure for many years, and most likely always will be. It works well most of the time and requires no special equipment.

The drawbacks are that it can be time-consuming and requires a helper, which we don’t always have. You also must make sure you don’t run out of fluid in the process, or you’ll be starting all over again.

The Master Cylinder

Brake master cylinders must be “bench”-bled prior to installing them. Most master cylinders come with a kit of hoses and fittings to connect to the outlet ports. The hoses are then run back to the filled reservoir. With the master cylinder secured in a vise, you can access the piston and use a tool to push it in to fully depress it, which forces the air out and up into the reservoir.

There are many reasons to do this. For one, many master cylinders are mounted at angles that can trap air and make bleeding on the car extremely difficult. Secured level in a vise eliminates this problem. It’s also much quicker. Usually, it only takes five to 10 short strokes to get the air out. When the cylinder is mounted in the car, it takes the full travel of the brake pedal for the same short stroke. It also saves fluid by recirculating it back into the reservoir.

The most important thing to remember is that air can still get trapped in the master cylinder during installation. Usually, it’s forced through the lines and out, but not always. If you’ve bled the brakes and still have a low or soft pedal, you may have air in the master cylinder. At this point, it’s easy to get out. With an assistant holding pressure on the pedal, crack the line fittings at the master cylinder. You’ll hear the sound of the air as it’s forced out. Some master cylinders have bleeder screws for this purpose.

Gravity Bleeding

Gravity bleeding is often overlooked, since the “standard” method over the years has a stronghold on the perception of brake bleeding. Gravity bleeding is simple: Fill the reservoir and open the bleeder screws. Sit back and relax. Gravity will pull the fluid through the system, and the air will travel along with it and out. When fluid continuously drips from the bleeders, your job is done. Theoretically speaking, gravity bleeding should always work, and it usually does.

Truth be told, I rarely use any other method. The problem with gravity bleeding is it can be slow. I usually let gravity do its thing as I clean up from the job. After I get fluid from each bleeder, I close them, pump the pedal a few times to seat the brakes, then open them one more time to release any remaining air. It’s almost foolproof.

Pressure Bleeding

Pressure bleeding is popular among professional technicians due to the speed of it, and the fact that you don’t need an assistant. The drawback is the equipment can be expensive, so you must use it all the time for it to pay for itself.

A pressure bleeder utilizes an adapter that attaches to the master cylinder, then forces fluid into and through the system. The main advantage to pressure bleeding is that it’s quick, but sometimes it’s also necessary. This is especially true on some newer vehicles with antilock braking systems (ABS). Air can get trapped in the ABS valving, and in some situations, pressure bleeding is the only method that will work. The high pressure compresses the air bubbles to the point where they’re carried through with the fluid, instead of hanging up in a crevice while the fluid flows by.

If you work on newer vehicles, at some point you will need a pressure bleeder. A final advantage to pressure bleeding is this equipment stores a volume of fluid, so you don’t have to worry about running out mid-process.

Vacuum Bleeding

A vacuum bleeder attaches at each bleeder screw and draws the fluid through the system. It’s just another way of doing it with the advantage of speed when compared to manual bleeding. Vacuum bleeding also is one of the cleaner ways to do it because you’re drawing the fluid through the system directly into a container. You don’t have to worry about catching the fluid that’s pushed out of the bleeder using other methods.

Auto-Refill Kits

It’s easy to run out of fluid when bleeding brakes. We’ve all done it. A popular option for manual, gravity or vacuum bleeding is a refill kit that connects to the master cylinder and feeds fluid into it through gravity. They usually have a large enough capacity for bleeding or changing the fluid. Are they necessary? No, just a convenience.

Final Tips

Some newer vehicles with ABS have the option to bleed the ABS modulator and valve assemblies with a scan tool. This uses the ABS pump to force fluid through the system. The advantage is getting air out of the modulator. This often is the quickest and most efficient way to do it, but generally it’s not mandatory if you don’t have the scan tool to do it. The same result can be had with a pressure bleeder.

There are two things that are frequently confused – a soft pedal and a low pedal – and it takes experience to recognize the difference. A soft pedal is caused by air in the system, and a low pedal is commonly caused by misadjusted drum brakes, so just be aware of this and don’t confuse the two. With the proper preparation and a little bit of patience, brake bleeding always should be the most routine part of the job.