On a mechanical level, it is easy to understand how brakes work. We all understand that brake fluid transfers force from one hydraulic component to another. But, how does this apply to how a brake pedal feels? This is where math is required.

On a mechanical level, it is easy to understand how brakes work. We all understand that brake fluid transfers force from one hydraulic component to another. But, how does this apply to how a brake pedal feels? This is where math is required.

You need only two simple math equations to commit to memory. First, the equation for calculating the surface area of a circle (i.e., the caliper or master cylinder piston) is pi (~3.14, π) times the radius squared.

Second, pressure (pounds per square inch, or psi) is equal to the force divided by the surface area. The rest of the math is just multiplication, division and addition/subtraction.

Pedal Ratio

Let’s start with the driver. In a sitting position, the average driver can comfortably generate 70 pounds of force on the rubber pad at the end of the brake pedal. The brake pedal is nothing more than a mechanical lever that amplifies the force of the driver. This is where the pedal ratio comes into play.

Pedal ratio is the overall pedal length or distance from the pedal pivot to the center of the pedal pad, divided by the distance from to the pivot point to where the push rod connects.

The optimal pedal ratio is 6.2:1 on a disc/drum system without vacuum or other assist method. This means that the 70 pounds the driver has applied now is amplified to 434 pounds (6.2 × 70 pounds) of output force. The problem is that the travel of the pedal is rather long due to the placement of the pivot point and master cylinder connection.

Brake Boosters

A booster increases the force of the pedal so a lower mechanical pedal ratio can be used. A lower ratio can give shortened pedal travel and better modulation. Most vacuum-boosted vehicles will have a 3.2:1 to 4:1 mechanical pedal ratio.

The size of the booster’s diaphragm and amount of vacuum generated by the engine will determine how much force can be generated. Most engines will generate around -8 psi of vacuum (do not confuse with inches of Hg, or mercury). If a hypothetical booster with a 7-inch diaphragm is subjected to -8 psi of engine vacuum, it will produce more than 300 pounds of additional force. Here is the math:

π(3.14) × radius(3.5)2 ≈ 38.48 in2 of diaphragm surface area × 8 psi (negative pressure becomes positive force) ≈ 307.84 pounds of output force

To keep things simple, let’s return to our manual brake example. The rod coming from the firewall has 434 pounds of output force. When the force is applied to the back of the master cylinder, the force is transferred into the brake fluid.

The formula for pressure is force divided by the surface area.

If the master cylinder has a 1-inch bore, the piston’s surface area is .78 in2. If you divide the output force of 434 pounds by the surface area of the piston, you would get 556 psi (434 pounds divided by .78 inches) at the ports of the master cylinder. Not bad for 70 pounds of human effort.

If you reduce the surface area of the piston you will get more pressure. This is because the surface area is smaller, but the output force from the pedal stays the same. If you used a master cylinder with a bore of .75 inches that has a piston that has .44 inches of piston surface area, you would get 986 psi at the ports for the master cylinder (434 pounds divided by .44 inches).

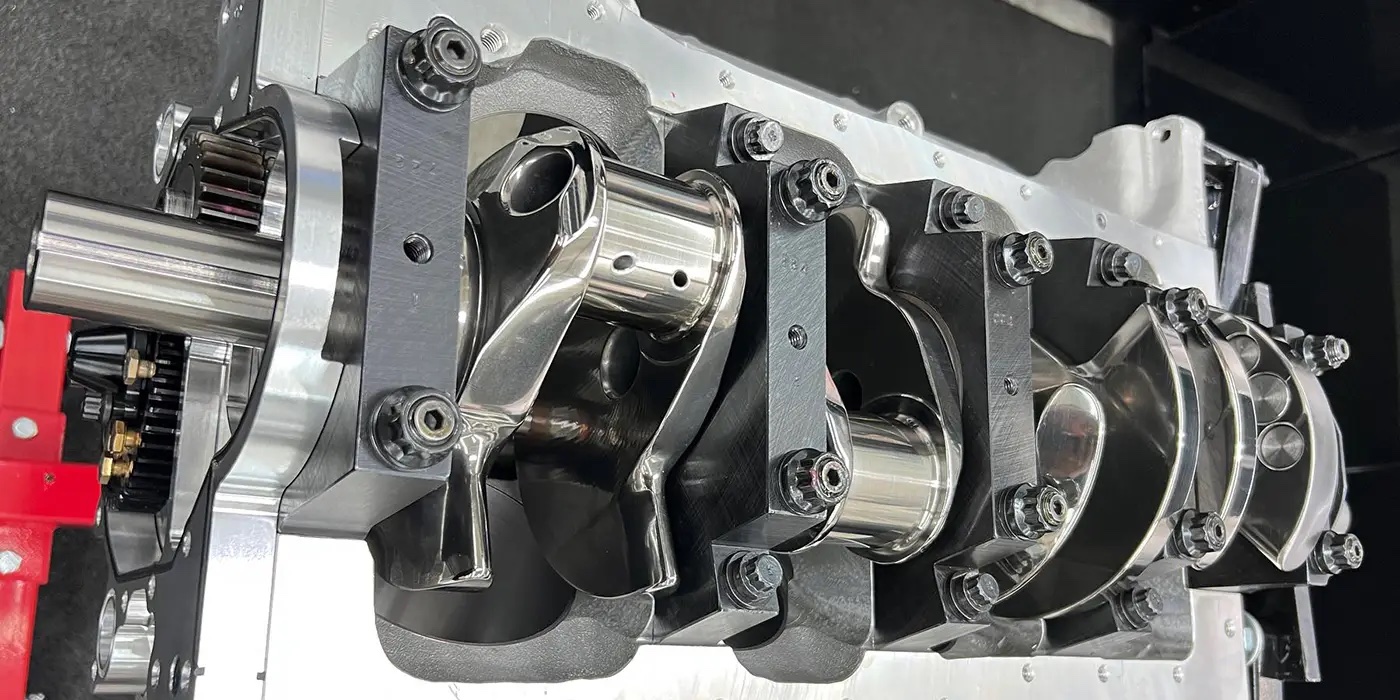

Calipers

Seventy pounds of force on a brake pedal can result in 556 psi of brake fluid heading to the calipers. So how does this pressure stop a car?

If the calipers are a single piston floating design with a two-inch diameter pistons (piston surface area = pπR2 × 2), we just multiply pistons surface area by 556 psi and surface area and we get 3,419 pounds of clamping force at both front calipers!

In our theoretical example above, we are ignoring some real world factors that influence the amount of clamping force. The reality of it is that not all of the 556 psi makes it to the caliper and some of the force is wasted flexing the caliper and compressing the brake pads.

Even if all of the pressure makes it to the caliper piston, some of the generated force is lost as the caliper flexes. This flexing can occur at the bridge or mounting points. Most floating caliper designs can have more flex. Opposed piston designs are typically stiffer. But, if the input pressure and piston area is the same for both designs, the calipers will generate the same theoretical forces.

If you try to improve a system by changing to larger calipers with more piston surface area or change the diameter of the master cylinder, you are upsetting the balance. Another factor in the system is the brake pad and how it acts under the force. If the backing plate flexes, braking force is lost as the friction area flexes and changes.

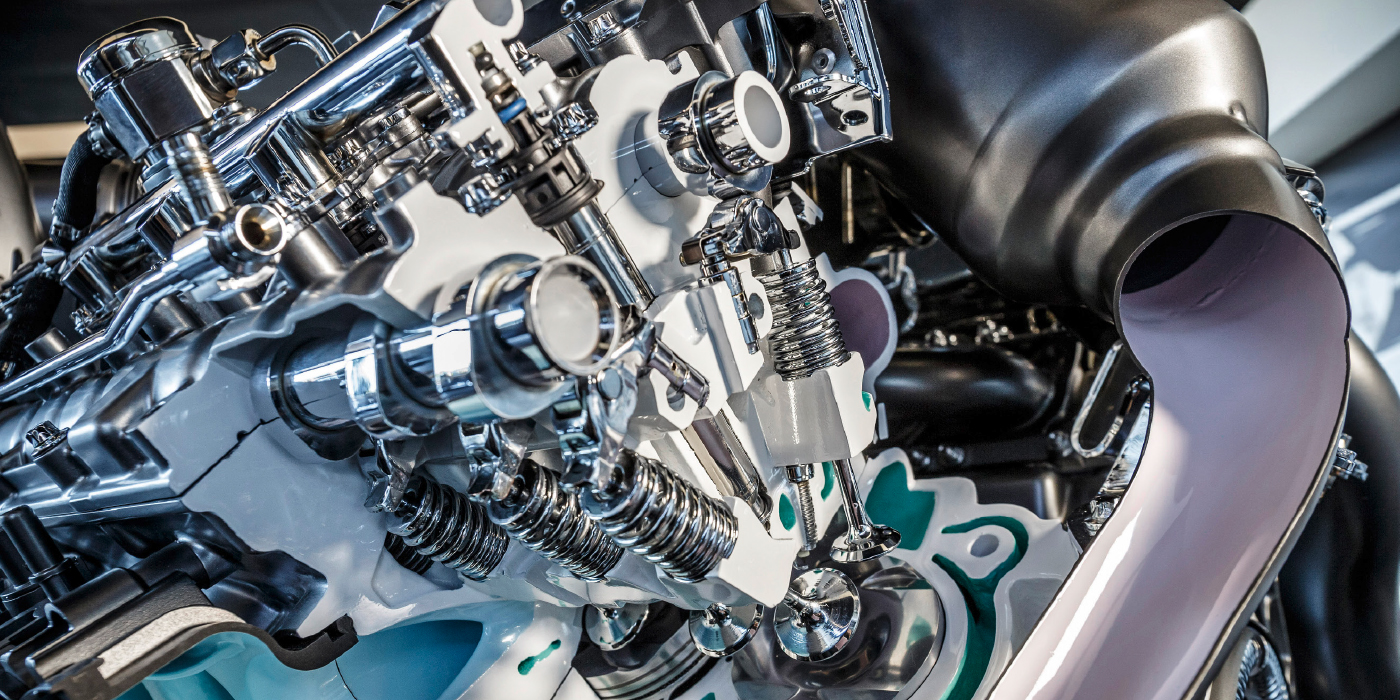

The clamping forces are used to generate friction that produces torque to stop the vehicle. This is where “coefficient of friction” comes into play. Basically, the coefficient of friction is calculated by dividing the force required to slide an object over a surface by the weight of the object. For example, if it takes 100 pounds of force to slide a 100-pound brake pad over a rotor, the coefficient of friction between the two materials is 1.0.

Clamping forces and the coefficient of friction are on one side of the equation and brake torque is on the other side. If you increase either variable, you are changing the amount of torque the system can generate.

In essence, engineers balance coefficient of friction with piston and master cylinder sizes to give the vehicle the right amount of stopping force and pedal feel. If you increase or decrease the coefficient of friction, you might be upsetting the balance.

Article courtesy Brake & Front End.