Fuel injection is as old as the internal combustion engine itself. However, many of the early systems proved to be somewhat troublesome and quirky. The carburetor, by comparison, was simple and dependable, and therefore the fuel system of choice for the majority of mass-produced vehicles through most of the 20th century.

For those who entered the automotive industry during the reign of the carburetor, fuel injection was so uncommon that as it began to make a comeback during the 1980s, it was largely misunderstood and tagged with the less-than-endearing term of “fuel infection.”

With the help of electronics and computer control, fuel-injection systems began to improve quickly and followed a course of evolution that introduced many different system designs. Suddenly, we were bombarded with unusual terms and acronyms like Jetronic, Motronic, TBI, MFI, GDI, TDI and many more. While it might have seemed confusing at first with so many different coined terms from so many different manufacturers, ultimately there are only two basic types of fuel injection.

Why Fuel Injection?

For efficient combustion to occur, fuel must be atomized first (broken up into the smallest particles possible) so it can mix with the air and vaporize. Only then will it properly burn inside the cylinder.

The job of a carburetor was simply to allow the air flowing through it to atomize the fuel as it draws it out of the various circuits. Carburetors work very well at doing this, but they also are inefficient in many ways, preventing them from remotely coming close to the efficiency required for the tightening emission regulations of the time.

This is where fuel injection proved itself a superior method of fuel metering. Fuel injection atomizes the fuel as it exits the tip of the injector. But even more importantly, with the combined advance in electronics and computer controls, it also provides precise control of the amount of fuel – a critical aspect for fuel economy and emission control.

Indirect Fuel Injection

Indirect means the fuel is injected and atomized before it enters the combustion chamber. Throttle-body injection (TBI), sometimes referred to as single-point injection, is a type of indirect injection in which the injector is located in a throttle body before the intake manifold. The throttle body looks similar to a carburetor and uses many similar components such as the intake manifold and air cleaner.

This was done by design, as it was the most efficient and quickest way for auto manufacturers to make the change to fuel injection, while utilizing many of the same components. Port, or multi-point, injection injects fuel into the intake runner just before the intake valve for each cylinder. Still a form of indirect injection because it occurs before it enters the combustion chamber, the advantage is the ability to precisely control the fuel delivery and balance the air flow into each cylinder, leading to increased power output and improved fuel economy.

Whether an engine is carbureted or fuel-injected, atomization of the fuel is critical for combustion. Many variables affect atomization, and even though a fuel injector initiates the process, the airflow and other objects around it will affect how well the atomized fuel mixes with the air and vaporizes. The location of the injector as well as the design of surrounding components are critical aspects of engine design.

TBI is at a disadvantage because the airflow is interrupted by the injector – another reason that port injection has the advantage and has made TBI obsolete on newer vehicles.

Diesel engines are fuel-injected because diesel fuel doesn’t atomize and evaporate like gasoline. It must be injected into an air stream at high pressure to atomize, and the turbulence of the air is an important factor in causing the air and fuel to mix.

Early on, due to the difficulties of creating an efficient direct-injection system, many diesel engines utilized a pre-combustion chamber that created the necessary turbulence for proper fuel atomization. The fuel was injected into this pre-combustion chamber, making these indirect fuel-injection systems as well.

Direct Fuel Injection

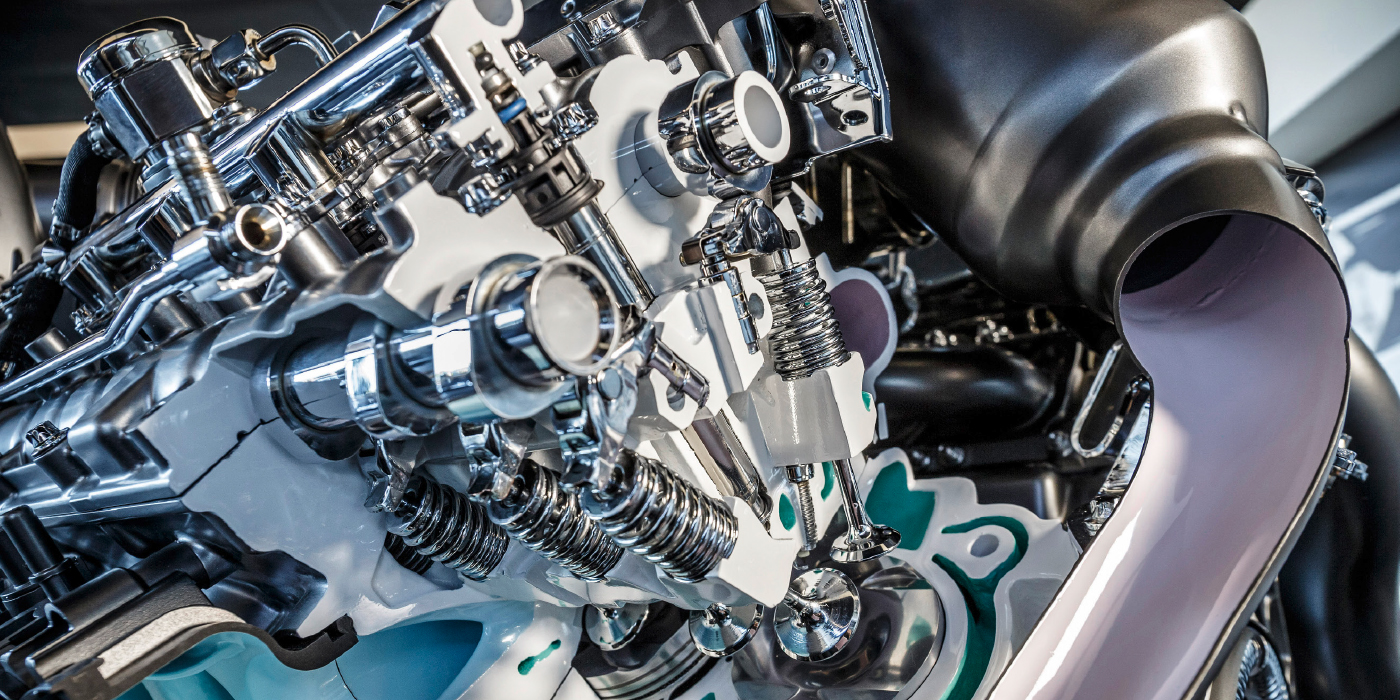

Direct means the fuel is injected directly into the combustion chamber. The challenge with this type of injection is the pressure inside the combustion chamber is much higher than that of the pressure in the intake manifold of an indirect-injection system.

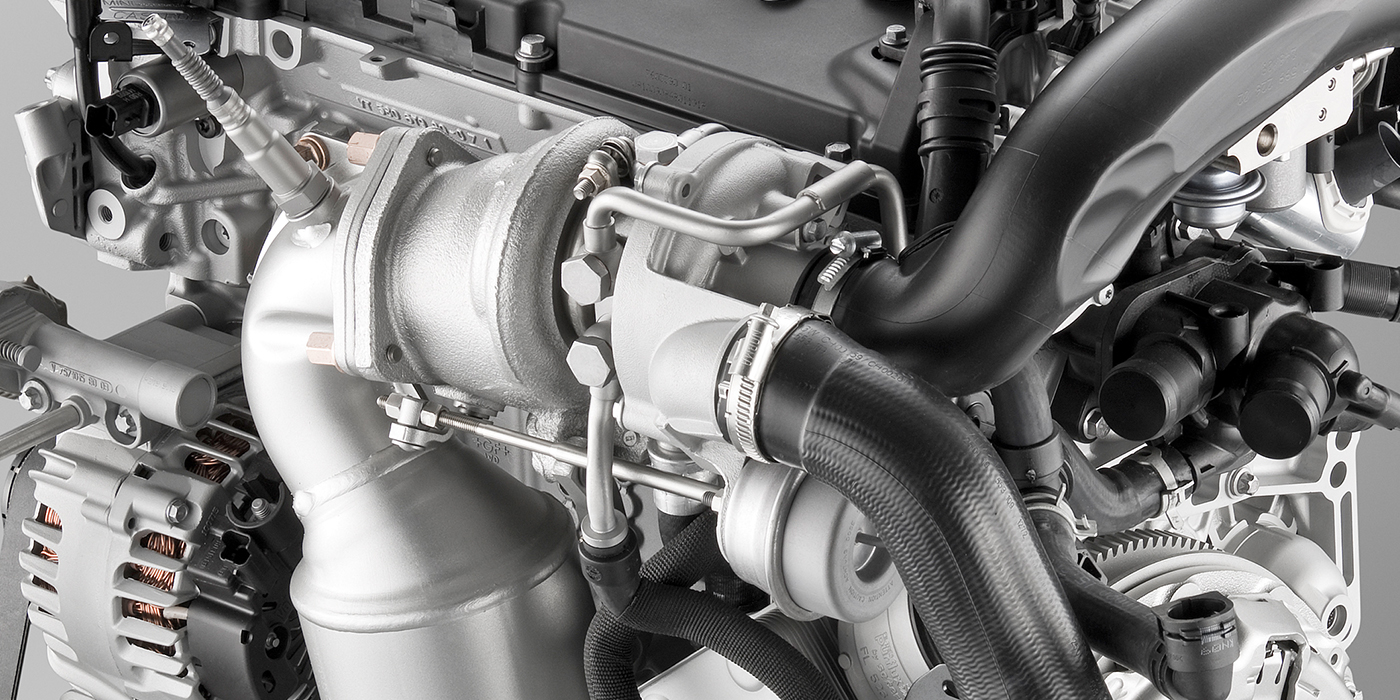

For the fuel to be pushed out of the injector and atomized, it must overcome the high pressure in the cylinder. Indirect systems have a single fuel pump in the tank that provides adequate pressure for the system to operate, usually 40 to 65 pounds per square inch (psi). Direct systems utilize a similar pump to supply fuel to the rail but require an extra mechanically driven high-pressure pump that allows them to overcome cylinder pressure. These systems usually operate at 2,000 psi or higher.

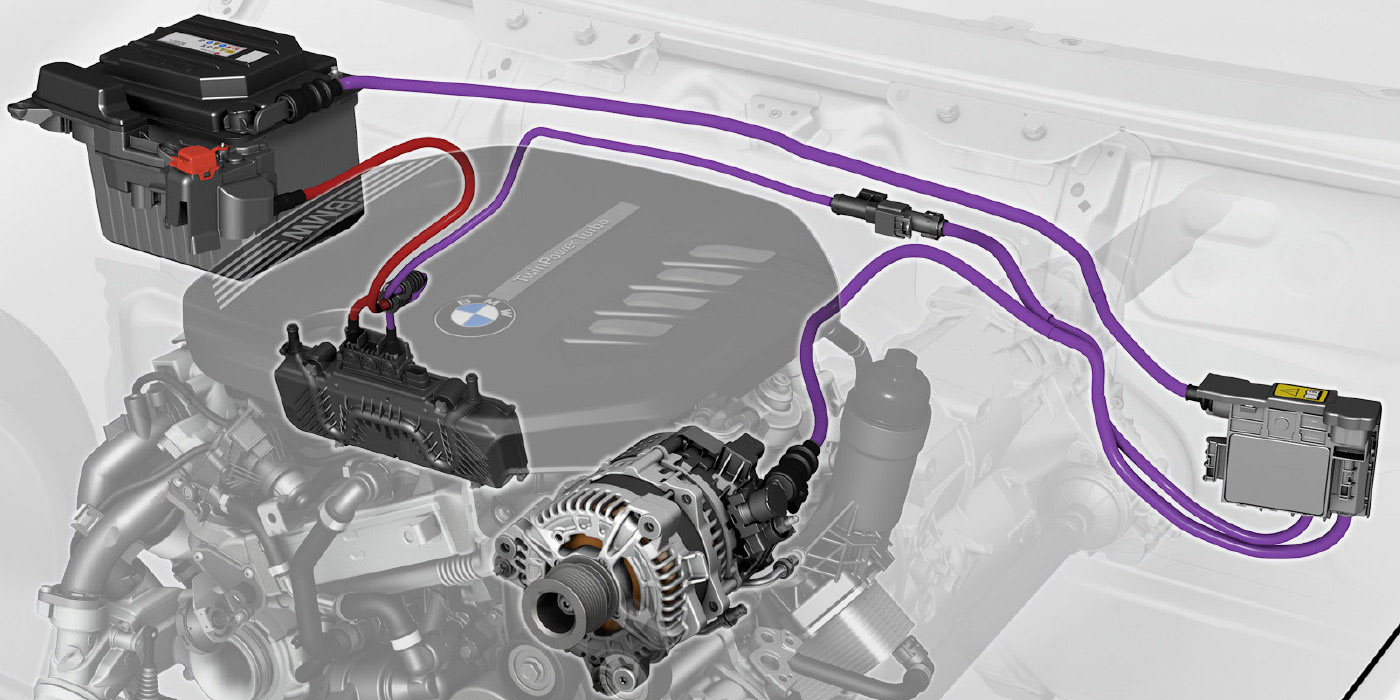

Direct-injection systems can be identified easily by the location of the injectors going directly into the cylinder head as well as the additional lines and mechanical pump, usually visible above the valve cover.

The primary advantage of direct injection is that there is less time for the air/fuel mixture to heat up since the fuel isn’t injected in the cylinder until immediately before combustion. This reduces the chance of detonation, or the fuel igniting from the heat and pressure in the cylinder. This allows a direct-injected engine to have higher compression, which itself lends to higher performance.

Another advantage is reduced emissions and fuel consumption. With indirect injection, fuel can accumulate on the intake manifold or intake ports, whereas with direct injection, the entire amount of fuel sprayed from the injector is the exact amount that will be burned, ultimately leading to more accurate control over the combustion process.

The overall performance and efficiency of direct injection can’t be matched. However, there are still some disadvantages to it when compared with indirect injection. One of the most well-publicized is carbon buildup on the back of the intake valves. Fuel is a great cleaner, and the fuel spray from a port-injected engine keeps the back of the valves clean. Without it, excessive carbon buildup occurs, leading to interrupted airflow into the engine, reduced performance and an expensive repair.

While not an issue for typical everyday driving, indirect injection is limited at high engine rpm because there simply isn’t enough time for the injector to release the fuel and for it to properly atomize. Since port-injected engines spray fuel before or as the intake valve is opening and complete vaporization occurs and the air is pulled into the cylinder, there’s no rpm limit with indirect injection.

Low-speed pre-ignition (LSPI) is a common term you may have heard, and it’s a problem that exposes another chink in the armor of direct injection. The piston and combustion-chamber design of a direct-injected engine is very specific to create the proper air turbulence to completely vaporize the fuel for combustion. At low rpm, the piston is not able to create the proper turbulence, leaving unvaporized fuel pockets that combine with contaminants from oil vapor and carbon buildup, leading to pre-ignition.

While this problem specifically occurs on direct-injected engines, it can worsen with some engine oils depending on the additives they contain. This is why new oils are advertised to prevent LSPI.

As engine technology advanced, diesel engines saw changes in piston and combustion-chamber design that allowed them to make the switch to direct injection and realize the same performance benefits.

So, your two basic types of fuel injection are indirect and direct. There are advantages and disadvantages to both. What’s next? The simplest solution in the book: dual injection. Now manufacturers are building cars with both. Computer control utilizes both systems to eliminate the weaknesses and exploit the strong points of each type of system. It’s the best of both worlds. Wasn’t that easy?

This article is courtesy of Counterman Magazine.